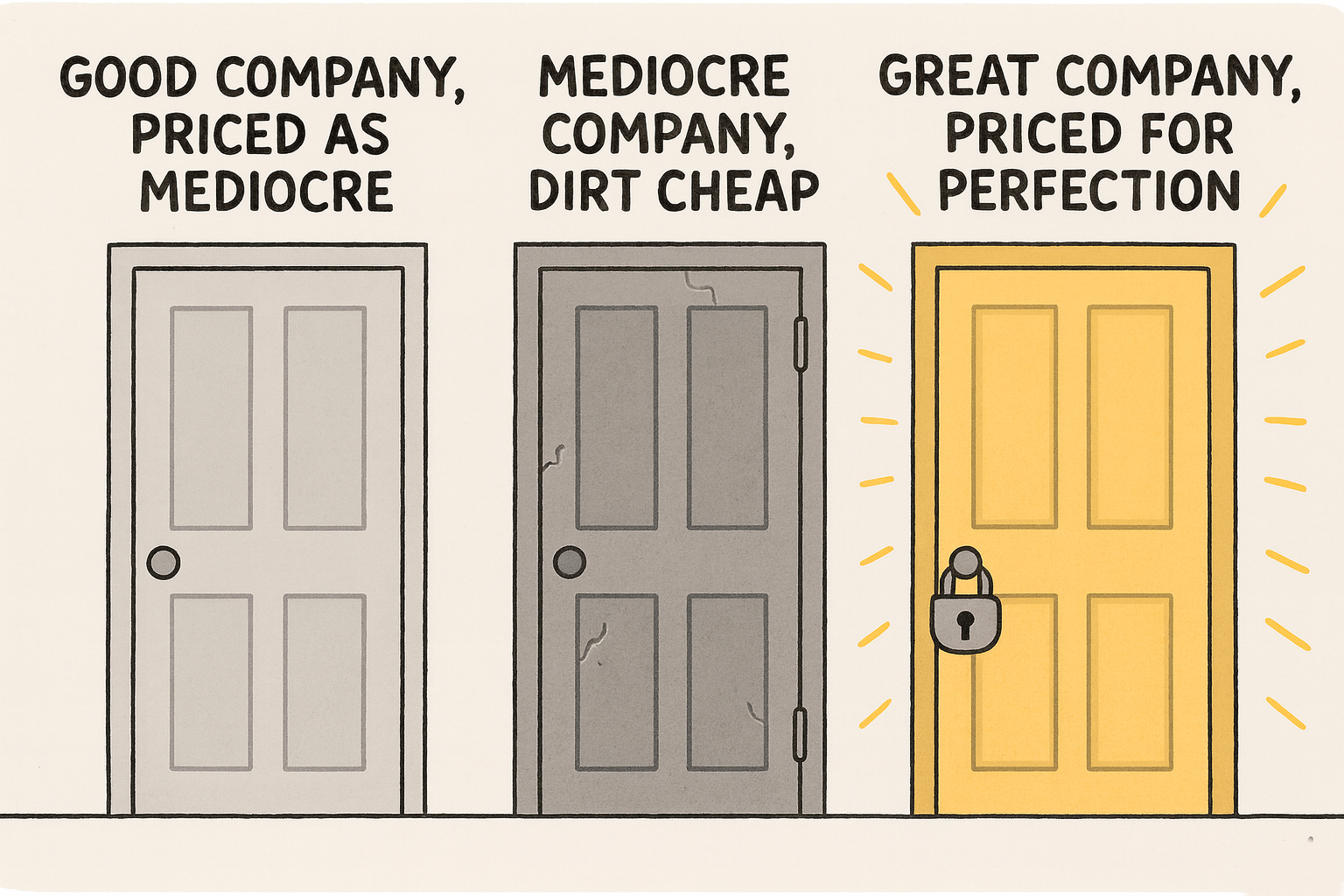

The Clean Hierarchy of “Cheapness”

A practical guide to understanding where real asymmetric opportunities hide

Investors often talk about “cheap stocks,” but cheapness is not a single category — it’s a spectrum. Some forms of cheapness signal opportunity; others signal danger. The key is distinguishing between quality mispricing and distress mispricing, because they lead to very different outcomes.

This hierarchy shows where the market is mispricing reality — and where asymmetric upside actually lives.

1. Good Companies Priced as Mediocre

The most attractive form of cheapness.

A fundamentally strong company — durable business model, healthy balance sheet, competitive advantages — can temporarily fall out of favor. The business remains solid, but the market prices it as if it’s merely average.

Characteristics

Quality: high

Price: discounted, but not “dirt cheap”

Expectations: low

Risk: moderate

Upside: strong if sentiment normalizes

This is the classic setup for asymmetric upside: the downside is cushioned by real fundamentals, while the upside comes from the market correcting its pessimism.

2. Mediocre Companies at Very Low Prices (“Dirt Cheap”)

The deeper, riskier form of cheapness.

A mediocre company — inconsistent earnings, weak competitive position, operational issues — can trade at extremely low valuations. The market is often pessimistic for good reasons. But sometimes the price overshoots reality, creating a potential bargain.

Characteristics

Quality: average or weak

Price: extremely low

Expectations: extremely low

Risk: high

Upside: possible, but depends on a turnaround

This is the realm of deep value. It can work, but it requires humility: many companies are cheap because they deserve to be.

The Asymmetry Core

The part that finally makes the whole model click

Asymmetry has nothing to do with whether a company is “good” or “mediocre.” It has everything to do with whether the price reflects the wrong probabilities.

When investors say:

“Look for situations where the market is underestimating the good outcomes and overestimating the bad ones,”

they mean:

Bad outcomes are priced as too likely, and

Good outcomes are priced as too unlikely.

This is mispricing — and mispricing is where asymmetry lives.

The market doesn’t reward you for:

liking a company

admiring a company

believing in a company

buying a “great” company

It rewards you for spotting wrong expectations.

A Tiny Example That Makes It Obvious

If the market thinks:

80% chance things go badly

20% chance things go well

But reality is closer to:

40% chance things go badly

60% chance things go well

Then the market is:

overestimating the bad, and

underestimating the good.

That’s asymmetry — regardless of whether the company is “great” or “mediocre.”

How This Fits the Hierarchy

Good company priced as mediocre

Market too pessimistic

Strengths ignored

Clean asymmetry

Mediocre company priced very low

Market maybe too pessimistic

Improvement underestimated

Riskier asymmetry

Great company priced for perfection

Market too optimistic

Risks ignored

No asymmetry

Now the entire framework aligns.

The 3‑Question Asymmetry Test

A 10‑second diagnostic for spotting mispricing

Ask yourself:

Are expectations already low? If the price is built on pessimism, downside is limited.

Is reality better than the price implies? If yes, the market is underestimating the good outcomes.

Is there a catalyst that could shift sentiment? Without a catalyst, mispricing can stay hidden for years.

All three yes → asymmetry Two yes → watchlist One yes → noise Zero yes → hype

The Essence in One Breath

You’re not hunting for great companies — you’re hunting for wrong expectations. Asymmetry appears when the price reflects the wrong probabilities.